Perhaps the most shocking infrastructure need for self-driving cars isn’t high-tech gadgetry or synchronized traffic control systems but something decidedly low-tech: paint. Cameras and laser systems depend on clearly defined lanes, and many of the nation’s roadways fail the “bright” test of having bright, preferably white, lines that are easy for cameras to “see.”

According to USA Today, one of the greatest challenges of making self-driving cars a reality is making critical road upgrades and infrastructure improvements as well as embedding roadway sensors. The situation is comparable to the beginning of the nation’s highway system, and it will take cooperation between states, cities, counties, businesses, automakers, and the federal government to build a national infrastructure for driverless cars.

Uncertainties Stymie Efforts to Create a Universal Autonomous Car System

Some states have been quick to embrace autonomous technology while others are content to hang back and see what happens with the first iterations of driverless technology. California, Michigan, Ohio, and Arizona welcome tests of robotic vehicles in their states, but other states are wary given the complex concerns about solving liability issues and integrating with public transportation systems.

Central Florida, which is a major tourist draw, plans to incorporate self-driving vehicles in its parks and family attractions. Florida Polytechnic University is building a 400-acre test track to simulate rural and urban driving conditions to test autonomous vehicles. The $100 million-dollar project is just one of the testing complexes under construction. Another facility at the Kennedy Space Center offers advanced testing of extreme environmental conditions such as flooding, smog, smoke, and fog.

There are also questions about whether “smart” cities and roads are entirely necessary. Uber and Google’s Waymo are rapidly developing vehicles that don’t depend on roadway upgrades. These vehicles will have their own sensing and mapping systems, so roadway upgrades may be less critical. States find it difficult to invest in infrastructure when it’s not entirely clear what’s needed.

The United States has yet to develop a comprehensive policy on driverless vehicles. A House committee is expected to consider 14 self-driving car bills in the near future, but the scattershot approach to making infrastructure upgrades throughout the country creates lots of ambiguities.

General Motors President Dan Ammann made some keen observations during his keynote address to the Economic Club of Chicago in February of 2017. “We are working very closely with a lot of cities, states, and the federal government, but we need to make sure the technology is able to work in the current environment. So we’re not depending on an improvement in infrastructure.”

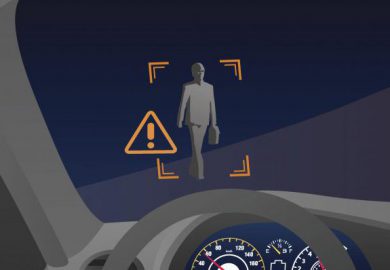

However, some states are leading the way in making proactive infrastructure improvements. Tennessee and other states are now installing fiber-optic lines in new roadways that can send electronic data to connected vehicles about any driving hazards ahead and other local traffic information.

California, where traffic deaths amount to about 10 percent of the nation’s total, has committed strongly to driverless tech. The state has licensed 30 or more companies to test self-driving vehicles in different driving environments across the state. In Palo Alto, 11 Silicon Valley intersections have embedded technology to inform cars about driving conditions and can even recommend a driving speed that allows cars to make every green light.

The Nation’s Roads Must Support Driverless Technology

A recent study by the National League of Cities found that only 6 percent of the largest U.S. cities have begun incorporating driverless technology into transportation planning. Until that changes, there won’t be enough support for self-driving vehicles to provide the proper infrastructure across the transportation spectrum. For example, it’s critical to study how driverless cars might react in construction situations where a work-zone environment could generate many unpredictable variables.

Driverless vehicles have moved with agile speed from a fantasy wish list to the real-world success of autonomous cars picking up passengers in Pittsburgh’s urban environment. However, there’s no guarantee that drivers will willingly give up control of their own vehicles. Marrying on-car autonomous tech with upgrades in infrastructure could help change that.